The story of the Ashgabat-Moscow trek is a famous one that really marked the precedent for preservation efforts of the purebred Akhal-Teke horse. This telling of “The Ashgabat-Moscow Horseback Ride” was shared online by Elena Panyushina (Елена Панюшина) originally in Russian here. It has been translated into English below. First there is an overview of the event, those involved, and its importance, followed by journal style entries of each major milestone along the 4300 km route over 84 days. Some of the experiences the horses and riders endured may be hard to read from modern sensibilities, but this trek truly tested the fortitude of these special horses in extreme conditions that may not have otherwise ever been tested. More significantly, this ride helped recognize the value of the Akhal-Teke (and Yomud) horses at a delicate time in their history when they may have been allowed to die out and instead became heroes among horses.

“What is especially important for the development of the breed, the race proved the superiority of purebred Akhal-Teke horses over Anglo-Teke horses.”

“Moscow threw flowers at the hooves of the Turkmen horses, which had covered themselves in glory with their unprecedented journey.”

The 1930s in the life of the young Soviet state were a time of extraordinary growth in productive forces. The country was gripped by enthusiasm for building a new and beautiful life. The Stakhanovite movement was spreading, gigantic new construction projects were being undertaken, and the mass physical culture movement was gaining unprecedented momentum. Records were being set in labor and in sports. One after another, world records were being established: flights into the stratosphere, non-stop air flights, off-road car rallies… Pilots, glider pilots, parachutists, skiers, and cyclists set records of courage and bravery. Equestrians were not left out either. These years were marked by numerous equestrian long-distance rides: solo and mass rides, individual and group rides, on horses of riding, trotting, and heavy draft breeds.

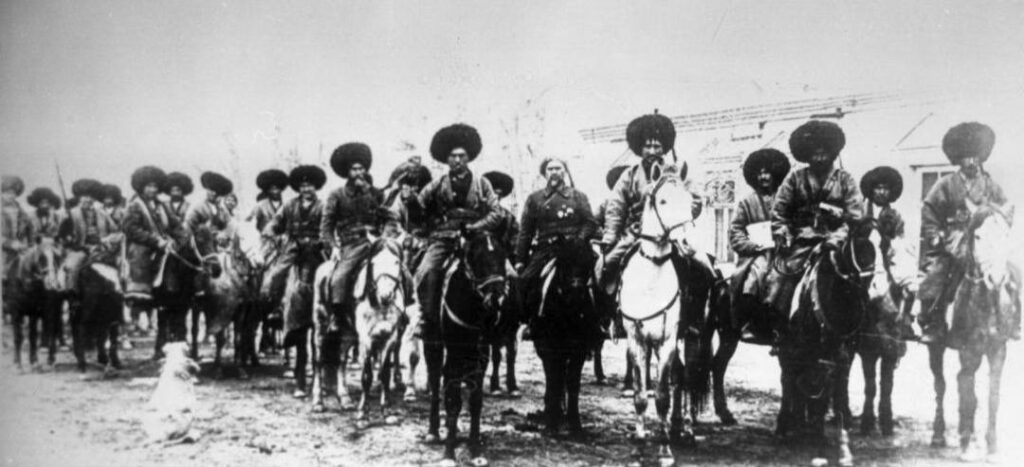

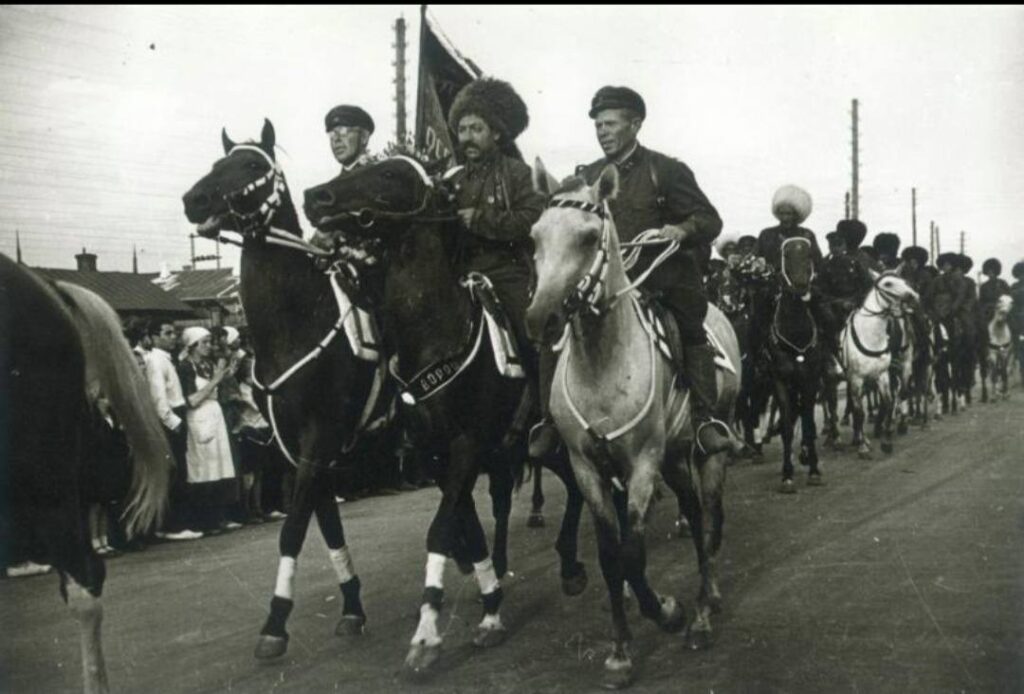

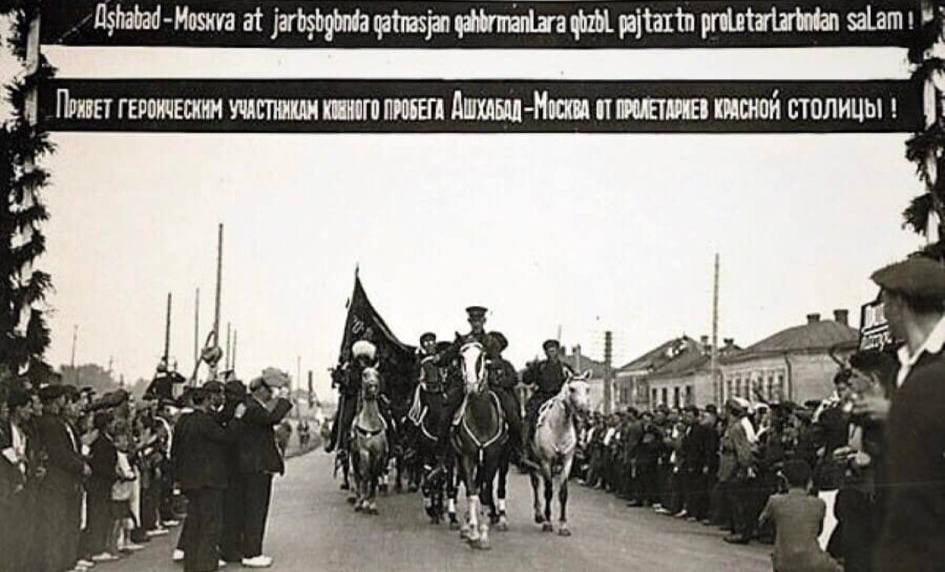

The most significant of these rides, which received widespread attention far beyond the country’s borders, was the journey of Turkmen horsemen on Akhal-Teke and Yomud horses from Ashgabat to Moscow, completed in 84 days in the summer of 1935. This ride was unusual in many ways. The route, 4300 kilometers long, passed through almost all of the country’s natural and climatic zones: desert, semi-desert, mountainous, steppe, forest-steppe, and forest.

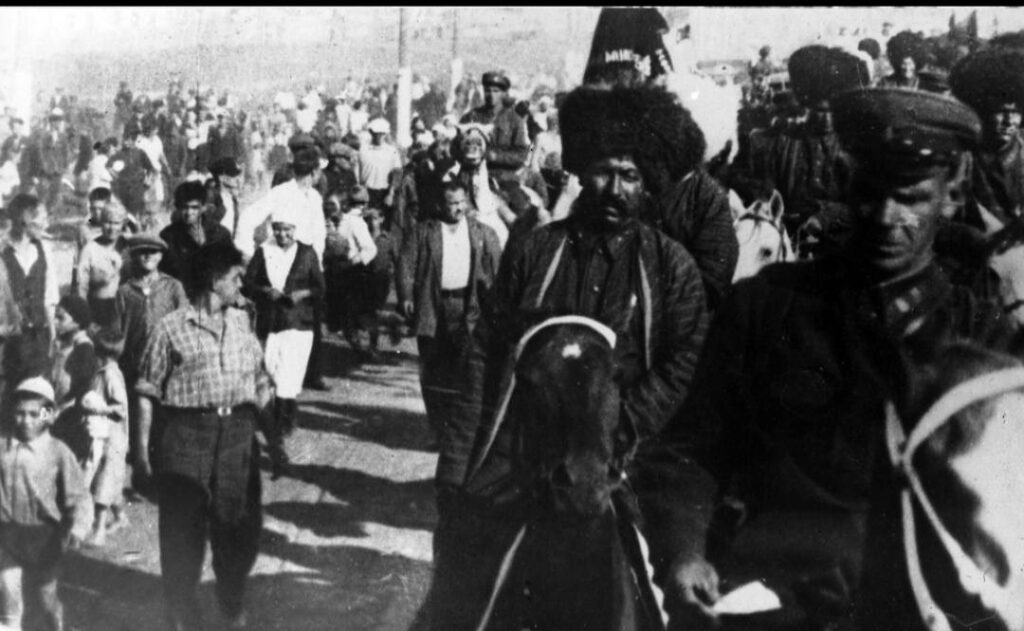

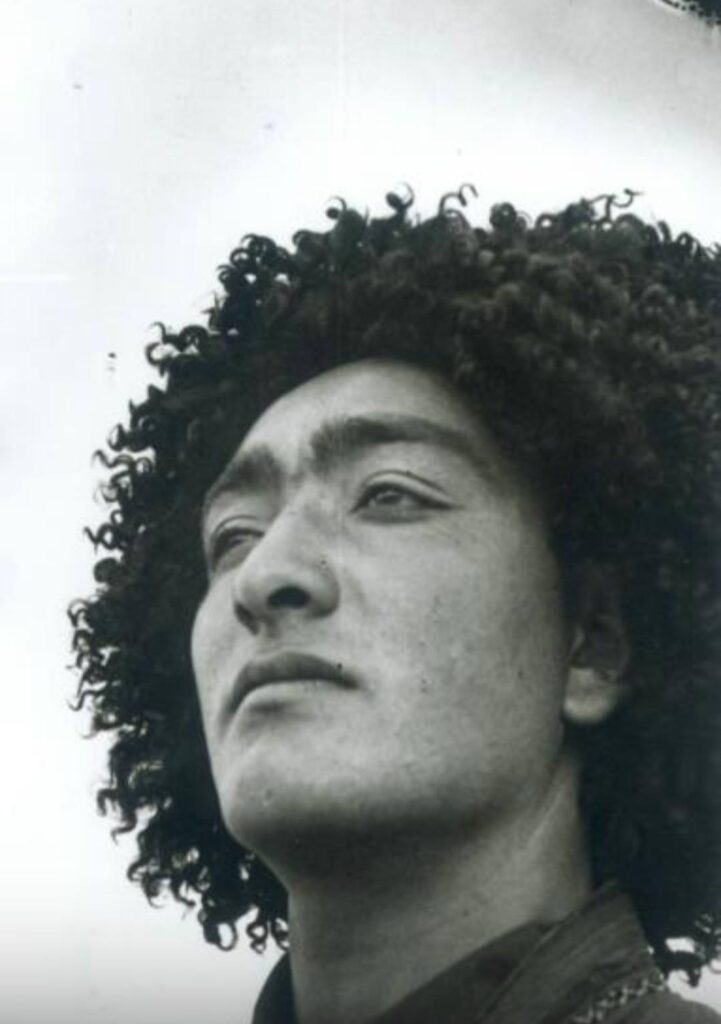

The participants were not athletes or cavalrymen, but the best representatives of the collective farm system. The youngest was 19-year-old Kurban Ovez Geldy; the oldest was 55-year-old Gabysh Mamysh, the party organizer of the race; the most famous was the guide Nepes Karakhan, who had traveled the Kara-Kum desert for 25 years without a compass, guided the expeditions of Fersman and Geller, and crushed the gangs of Junaid Khan; also, Bek Murad Anna Murad fought against the Basmachi for many years. But the most outstanding aspect was the example of courage and endurance shown by the riders and their horses. As M. I. Kalinin said in his welcoming speech in the Kremlin: “In this race, the collective farmers showed high discipline and skill in handling the horses they raise.” The race was meticulously prepared. All the riders underwent a medical examination. The horses were also carefully selected. A scientific program was developed: body temperature, pulse, and respiration were measured before and after the daily trek, blood samples were taken, and individual feeding rations were compiled. Taking into account the loss of salt through sweat during long journeys, up to 50-60 grams of salt were added to the feed daily. The horses were shod with different types of horseshoes – military, lightweight, and so-called “Eastern” horseshoes – in order to determine which ones were best suited for heavy loads.

The riders, along with the scientists accompanying the race, were also responsible for observing the horses. They were given an additional task: to acquire zootechnical knowledge, as they were expected to return as managers of horse breeding farms. The race had great international significance, passing through the territories of many Soviet republics and autonomous regions, and the Turkmen collective farmers experienced genuine hospitality and support from Soviet people of various nationalities. “Everywhere the race was accompanied by a demonstration of truly fraternal feelings of the peoples inhabiting the Soviet state, in all its national diversity” (M. I. Kalinin, ibid.). It is impossible not to mention the military-patriotic significance of the race – the endurance and strength of the horses, and their suitability for cavalry service, were tested in harsh conditions. “Not so long ago, some considered the Turkmen horse ‘too frail’ and therefore supposedly unsuitable for cavalry in the European part of the Soviet Union. But now the valiant winners of this gigantic race have proven the incorrectness of these views,” noted K. E. Voroshilov. And, what is especially important for the development of the breed, the race proved the superiority of purebred Akhal-Teke horses over Anglo-Teke horses.

Zootechnician Gavrilov wrote in “Turkmen Spark”: “…there was an opinion, even among specialists, that the Akhal-Teke horse was not suitable for long distances. The Ashgabat-Moscow race showed that the purebred Akhal-Teke and Yomud horses proved to be much more resilient and less demanding than the Anglo-Teke horses. Purebred Akhal-Teke horses: Arab, Dorkush, Alsakar, Titanic, Al-Kush and others easily covered up to 4000 kilometers, while the half-bred stallions Dor-Depel and Burnok deteriorated significantly.” In one of the publications in the same newspaper on July 6, N. Putilin emphasizes: “The Yomud and Akhal-Teke horses are doing excellently, the Anglo-Teke horses are doing worse,” and further: “Contrary to general fears, the rocky soils of Ustyurt did not harm the Akhal-Teke horses.” The collective farmers of the K. E. Voroshilov collective farm, sending their leading workers Bek Murad and Ashir Kuli on their best horses – a purebred Arabian and a half-bred Dor-Depele – instructed them to present the best horse to Voroshilov. “By sending these horses, the collective farm wanted to find out which type of horse should be bred: a purebred Akhal-Teke or one with mixed blood.” Today everyone knows that the Arabian (or was it Budyonny?) was given to Voroshilov (read “The White Horse of the Great Victory”).

Resolution

The Order of the Red Star was awarded by the Central Executive Committee of the USSR “For the unparalleled equestrian transition in the history of cavalry” to: S. P. Sokolov, head of the equestrian transition, commander of the NKVD border troops; E. R. Laman, deputy head of the transition, instructor of Osoaviakhim and twenty-eight collective farmers-shock workers: Nepes Karakhan (collective farm named after Voroshilov, Erbent district), Gabysh Mamysh (collective farm named after Atabaev, Tedjen district), Sapar Kuli Sakhat Berdy (collective farm named after Stalin, Tedjen district), Yanar Anna Oraz (collective farm “Udarnik”, Geok-Tepinsky district), Babaliev Mered (collective farm “Kizyl-Guch”, Mervsky district), Juma Nury (collective farm named after Atabaev, Mervsky district), Akmurad Kadyr (collective farm “Shura”, Mervsky district), Chary Kary (collective farm “Teze-Yol”, Bayram-Ali district), Sapar Alty (collective farm named after Atabaev, Tedjen district), Anna Geldy Sakhatli (collective farm named after Chary Velikov, Tedjen district), Berdy Ady (collective farm “Kizyl Baidak”, Kara-Kalinsky district), Illi Tashli (collective farm “Kizyl Yulduz”, Kara-Kalinsky district), Baba Durdy Murad (collective farm “Military”, Geok-Tepinsky district), Pasha-Kuli Poky (collective farm “Batrak”, Geok-Tepinsky district), Samat Haidar (collective farm “Military”, Geok-Tepinsky district), Ovez Geldy Kurban (collective farm “Kizyl Artel”, Geok-Tepinsky district), Atash Anna Aman (collective farm “Daihan Birleshik”, Ashgabat district), Bek Murad Anna Murad (collective farm named after Voroshilov, Ashgabat district), Mered Muhammed (collective farm “Daihan-Birleshik”, Ashgabat district), Anna Kurban (collective farm named after Kalinin, Ashgabat district), Ashir Kuli Bek (collective farm named after Voroshilov, Ashgabat district), Ak-Telpek Nagy (collective farm named after Popok, Kunya-Urgench district), Batyr Kazak (collective farm “Communist”, Ilyalinsky district), Babajan Shukur (collective farm named after. Akmamed Baba (Kolkhoz “Socialism”, Takhta district), Essen Khadyr (Kolkhoz named after the GPU, Takhta district), Kurban Durdy Aman (Kolkhoz “Yakhtalyk”, Takhta district), Seid Shekhi (Kolkhoz “Azat Turkmenistan”, Geok-Tepe district).

The collective farms that raised the horses were awarded with trucks. Seventeen participants of the trek from the escort group were awarded a certificate from the Central Executive Committee of the USSR. Among them were cinematographer P. A. Pyatkov, who filmed the most significant stages of the trek across the Ustyurt steppes and the western spurs of the Mugodzhar mountains, which were included in the film “Heroes of Collective Farm Turkmenistan”; correspondent of the newspaper “Turkmenskaya Iskra” N. I. Putilin, who supplied the editorial office with detailed information from the route; and medical doctor V. D. Sokolov, head of the scientific group. Let’s turn the yellowed pages of this newspaper, consult the diary of the expedition commander, and become witnesses to those heroic events. May 30th. 28 horsemen, shock workers from the collective farms of Turkmenistan, led by experienced commanders of the Red Army, are setting off today on an unprecedented journey on the collective farm horses of our republic…

June 2nd. From Ashgabat to Bahardok is 80 km. We covered this distance in two days. An inspection of the horses showed that they are adapting well to the journey. Further on, we will travel 60 km a day, and in the waterless areas, up to 120 km a day, as planned in the schedule.

June 4th. Yesterday the temperature reached 60 degrees Celsius, and they are promising even higher temperatures today. “Conserve water!” Each rider, in addition to their flask, has a special water bag. There is a strict rationing of water for the horses. The people are training themselves to drink only with permission, in small sips.

June 8th. Darvaza. Sulfur plant. Today, by lunchtime, we reached Darvaza. Darvaza, translated from Turkmen, means “gate.” Two hills in this area, where sulfur is mined, resemble gates. Water is scarce here at the plant as well. For our sake, the water supply has been increased. But the water here is salty, and the horses refused to drink it. We had to force the horses to drink by pouring the water into their noses. You should have seen how they suffered, but we had no other choice.

June 9th. From Darvaza begins a 350-kilometer journey completely devoid of water. In 1.5 days, using two vehicles, the communists and Komsomol members, interrupting their rest day, established three bases with fodder, water, and provisions. Along the way, they constantly had to break down saxaul bushes and lay down a road for the vehicles.

June 12th. At 1 a.m., the detachment reached the borders of the Kara-Kum Desert, having overcome the most difficult stage in three days. Daily marches reached 90 km, and they traveled in the early morning and late evening with short stops for sleep.

June 19th. The detachment reached Urga – a tiny settlement by the Aral Sea under the steep cliffs of Ustyurt. The last 90 kilometers were through continuous swamps. Swarms of mosquitoes surrounded us even before we entered the valley. The horses were dressed in protective coverings beforehand, and we armed ourselves with branches. The whistling of these branches and the thin buzzing of the mosquitoes seemed to drown out even the splashing of the water.

June 27th. Isolation from the base and the lack of gasoline caused an unforeseen four-day stop on the shore of the Aral Sea. We had to manually lift 800 buckets of water from a small stream onto the 300-meter plateau. A competition was organized between the two detachments. The first detachment, commanded by Yanar, won. The strongest man in the detachment, Samed Haidar, lifted an entire barrel. The results of the competition were published in the “wall newspaper.” In the evening, the vehicles with fuel arrived.

July 8th. Emba State Farm. The thousand-kilometer journey across the Ustyurt Plateau is no less difficult than crossing the Kara-Kum Desert. After the forced “stop,” we had to make up for lost time – for 5 days we traveled 80-100 km a day. In 12 days of travel across Ustyurt and Mugodzhar, we did not meet a single person.

July 9th. Today we decided to give the horses a rest, and tomorrow we will enter Aktobe. We were falling behind schedule, so we tried to bypass the frequently encountered settlements, where people tried to detain us to feed us. On the road we were starving, and here we are suffering from overeating. As we approached Aktobe, night fell. In the darkness, one of the riders and his horse fell into a shallow pit. Fortunately, they did not sustain serious injuries and continued their journey.

July 10th. In Aktobe, we were met by our Kazakh friends, who generously treated us to beshbarmak and kumis. After lunch, we decided to continue our journey. However, the residents of the “Sotsialdy Zhol” collective farm had covered the entire road with beautiful Turkmen carpets, on which tablecloths were spread with bowls of pilaf and beshbarmak, and cups filled with kumis. We hadn’t planned to stop, so as not to fall behind schedule, but the invitation was formulated quite insistently: “If you don’t want to sample our treats, then go straight through the table, if you have the courage to do so.” Of course, we didn’t have the courage.

July 17th. The incessant rains turned into a real disaster, transforming ravines into raging rivers, which we had to cross almost by swimming. The horses are having a very hard time. We cannot enter the nearest settlements due to outbreaks of animal diseases (epizootics). We are all completely soaked – both the horses and us. The tents and other things loaded on the truck have turned into soggy rags. We are amazed by the endurance and health of the horses, who stubbornly continue towards their intended goal.

July 20th. Buzuluk. It has been raining for two days. There are no stables in the city, so we had to leave them in the rain, covered with blankets. We decided to shorten the daily distances to 67 km. We also reduced the feed ration, otherwise the horses’ stomachs wouldn’t be able to cope.

July 23. Kuibyshev. A crowd of workers solemnly greeted us outside the city. Then there was a rally in the city center, in the square, near the monument to Chapayev. The collective farmers brought their horses to show us. 105-year-old Grandpa Larion, holding a large loaf of bread, gave a speech: “…Our collective farm is the best you can find. The people are fiery. There’s plenty of bread. There are 4 of us, and we still have about 40 poods left from last year. Last year I earned 100 workdays. This year – almost 60 already. I weave bast shoes. I run around the fields. Wherever I see people working poorly, I straighten them out. I’m a quality inspector! I’m a restless old man. They’re afraid of me on the collective farm.” On the same day, airplane rides were arranged.

August 4. Mokshan. We are traveling through the forest. The forests here amaze the horsemen. In their homeland, they are used to gnarled trees with crooked trunks. “So, this is where telegraph poles grow,” they say and smile.

August 16th. Ryazan. We arrived here in the evening, and a rain greeted us. This time a pleasant one – a rain of live flowers. The reception was solemn; only the horses were slightly panicked by the flowers.

August 19th. Bronnitsy. Moscow is getting closer and closer. Soon we will see it. The horses are in perfect condition, and so are the people. There are no stragglers. One more day, and we will say: “Hello, Moscow, the capital of our great homeland! Greetings to the city that has become a symbol of the liberation of the working people of the whole world.”

August 22nd. At the Abel’manovskaya outpost. Before entering the coveted city of Moscow through the checkpoint, they paid tribute to the customs of their homeland. The custom requires that a horseman, setting out to visit people dear to his heart, adorn his horse with the most precious decorations. Each of them hung on the chests of their Akhal-Teke and Yomud horses the name of their collective farm, embroidered in gold on crimson velvet horse trappings. They carried this name like a banner across the shifting sands of the Kara-Kum desert, across the gloomy Ustyurt plateau, through the Kazakh steppes and the wheat fields of the Middle Volga, to the pine forests surrounding Moscow. Moscow waited at the Abelmanovsky checkpoint; the multi-thousand-strong, multi-voiced Moscow, stretching like a ribbon along the streets, waited for the dear guests with flowers in their hands at the gates of houses, on sidewalks, in windows, and even on rooftops; Moscow threw flowers at the hooves of the Turkmen horses, which had covered themselves in glory with their unprecedented journey.

Additional sources and for photo credits:

@-.- #russiainphoto.ru.

@-.”История Коннозаводства.